What is the European Union?

The European Union (EU) is a group of 28 European countries. These countries are known as ‘member states’. The EU is like a ‘club’. Member states follow rules, pay dues, and have access to benefits.

The EU’s powers and authority come from its member states: it can do only the things that its members have agreed it should be able to do. In that sense, it is no different from other international organisations, such as the United Nations or NATO.

However, the EU is different to other international organisations in two key ways.

First, the EU is involved in almost all areas of public policy (though to varying degrees). For example:

- It runs the Single Market and Customs Union, which you can read about in Paper 1.2: Trade: How It Works Today.

- It makes most major policy decisions relating to farming and fishing.

- It does a lot of regional development work in poorer parts of the EU.

- It encourages cooperation between countries on issues such as foreign policy, international aid, security and defence, and criminal investigations.

- It runs the Euro currency for the countries that use it. The UK is one of nine EU countries that don’t use the Euro.

Second, the EU has institutions that in some ways make it look more like a country than an international organisation. In other international organisations, key decisions are made by the governments of the member states meeting together. This happens in the EU. But in the EU decisions are also made by the European Parliament. The European Parliament is unique. It is the only international body in the world whose members are chosen directly by ordinary voters. The UK has 73 Members of the European Parliament (MEPs), who are elected every five years.

A Little History

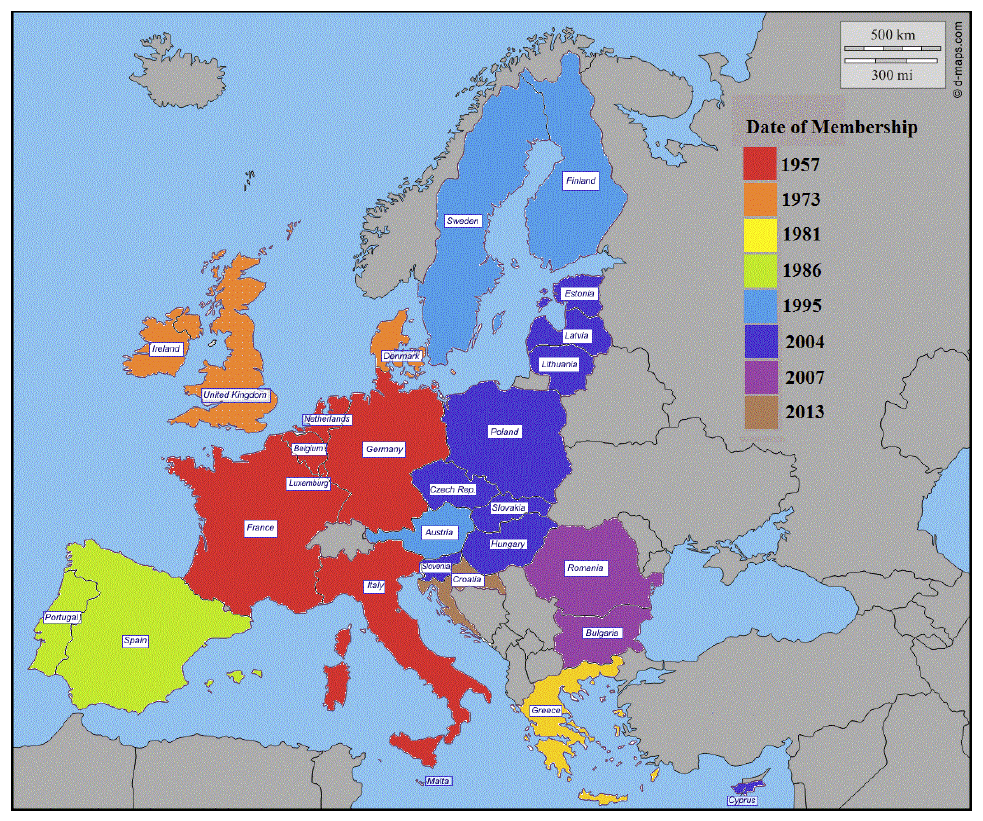

Today’s EU has emerged from what used to be called the European Economic Community (EEC). The EEC was founded in 1957. It was turned into the European Union (EU) in 1993.

When it was created, the EEC had just six members: France, West Germany, Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg. They had begun to work together a few years earlier, when they started to coordinate coal and steel production. They saw European integration as a way to encourage reconciliation and economic growth after the Second World War. During the Cold War period (up to around 1990), they also saw the EEC as an important defence against external threat.

In 1973, the UK, Ireland, and Denmark joined the EEC. The fall of authoritarian regimes in southern Europe allowed Greece to join in 1981, and then Spain and Portugal in 1986.

The biggest growth in membership took place after the Cold War ended at the start of the 1990s. First, German unification in 1991 increased the EEC’s territory. Then the previously neutral states of Austria, Finland, and Sweden joined in 1995. After much longer negotiations, eight former communist countries – the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia, and Slovenia – joined in 2004, together with Cyprus and Malta. Bulgaria and Romania joined in 2007. Finally, Croatia became part of the EU in 2013, bringing the total number of members to 28.

Currently, Albania, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, and Turkey are candidates to join the EU.

You can see how the EU has expanded over time in this map:

HOW DOES THE EU WORK?

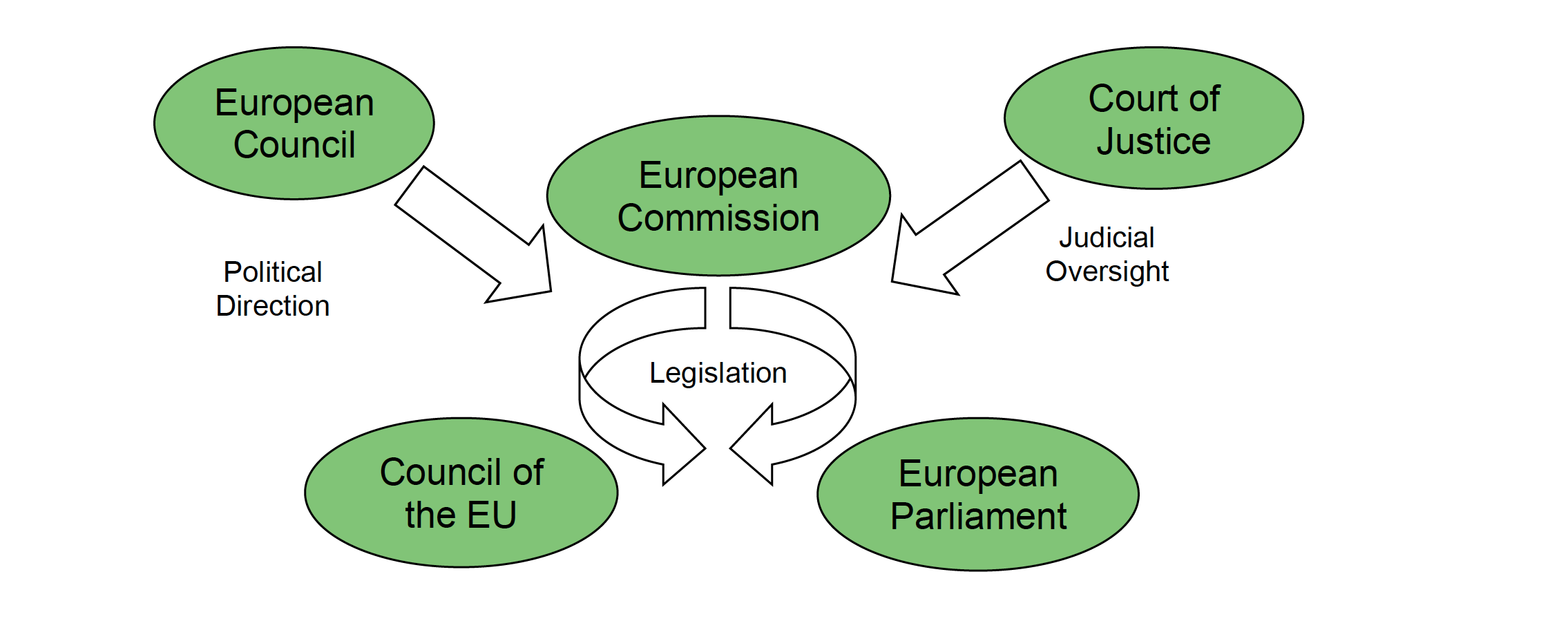

The EU has four key institutions:

- The Council of the European Union, where ministers from the national governments of all the member states meet together. When the prime ministers and presidents are meeting, this is called the European Council.

- The European Parliament, which is directly elected by EU citizens.

- The European Commission, which manages the EU’s work. It is the EU’s civil service.

- The European Court of Justice (ECJ), which deals with resolving disputes.

Together, these institutions make decisions. Exactly how they do this varies from policy to policy. The most common route (known as the ‘Ordinary Legislative Procedure’) has the following key elements:

- The Commission makes a proposal for legislation, based on consultation with member states and other interested people or groups.

- The Council and the European Parliament both consider the proposal separately. If they agree with the proposal, it becomes law.

- If either the Council or the Parliament disagrees, then the Commission tries to make adjustments, before passing it back to the Council and Parliament.

- If that still doesn’t produce agreement, representatives of the Council and Parliament meet to seek compromise. Any agreement has to be approved by both sides before it can become law.

Member states vote in the Council on whether to approve new legislation. It is not enough for a majority of the states to support a measure. Support has to be wider than that:

- In most cases, 55 per cent of states representing 65 per cent of the EU’s population have to support a proposal before it can become law.

- In some more sensitive policy areas, all of the member states have to agree before a proposal can be adopted. That includes, for example, decisions on finances or foreign policy.

The European Parliament was originally a body to be consulted over proposals. But it has gradually gained more powers, and its approval is now needed before laws can be passed. Yet it still is not a parliament in the usual sense. It cannot propose a new law by itself. Nor can it change taxes.

Most decisions are implemented by the member states, not by the EU itself. The Commission oversees implementation, checking that states do what they have signed up to do. When this does not happen, a case can be made to the ECJ, which has the power to issue fines.

Download 3-1 What is the European Union