From Labour announcing that they will back single market membership, at least for a transition period, to the Conservatives setting out key negotiating positions, we are beginning to get a picture of what post-Brexit Britain might look like.

The only question is: where do the public fit into this?

After every announcement we’ve seen talk, on both the left and right, of betrayal — a word that suggests parties were handed a clear set of instructions on how exactly to leave the EU.

Yet Brexit barely came up in the election campaign. So how do we actually know, beyond erratic polling snapshots, what voters want?

Surveys and focus groups can offer only a tiny glimpse of the public’s views on the highly complex and contested decisions that need to be made, on everything from the customs union to the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice.

But when other countries see rifts opened or aggravated by big constitutional questions, they are increasingly turning to an interesting model for closing the gap.

That model is the citizens’ assembly. Ireland’s constitutional convention, established to look at a swathe of constitutional issues, is what led to the legalisation of equal marriage. Its ongoing citizens’ assembly could do the same for abortion.

Brexit, arguably the most pressing constitutional issue of today, merits a similar concerted effort to create an informed conversation.

Leading universities and civil society organisations, funded by the Economic and Social Research Council’s UK in a Changing Europe programme, are trying to do that — to put voters’ voices into the Brexit debate.

This weekend the first citizens’ assembly on Brexit will begin, in a bid to bridge the Brexit divide and ensure the public’s voices are heard in the process of Britain leaving the EU.

To do this, we’ve convened a broad cross-section of citizens to ensure that the assembly reflects the different views and diverse make-up of the UK. We have worked with ICM, the polling company, to recruit a balanced group of participants.

The appetite to be involved is strong: ICM has been “stunned” by the levels, in fact.

From that, we have recruited a diverse sample of citizens to take part in the assembly and provide the first example of informed public deliberation on what form Brexit should take.

There are some unlikely bedfellows backing this, showing the potential to unite seemingly irreconcilable sides, from Will Straw to Bernard Jenkin, Harsimrat Kaur to Chuka Ummuna. The key part though — citizens being on board — means we have a powerful alliance for adding more democracy to this country-changing process.

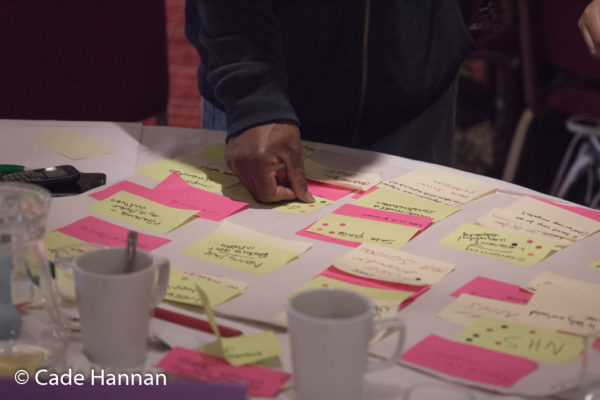

The assembly is meeting over two weekends (starting September 8 and 29) in Manchester, with members hearing about the options for Brexit, putting their questions to academics and experts from all sides of the debate and deliberating among themselves on what they have heard.

Crucially, the assembly will then agree recommendations that will be handed directly to those in power.

This is the first real opportunity for citizens on all sides to engage in the nitty gritty, the deep policy stuff that seemed to be missing from this year’s election.

Nor are we starting from scratch. The team behind the assembly conducted the UK’s first ever citizens’ assemblies on local devolution in Sheffield and Southampton in late 2015. We were blown away by the level of detail in the talk about this quite technical issue.

We have faith that if the public can do that on something like local devolution, they will be just as committed and inspiring on Brexit.

Public involvement in major constitutional issues shouldn’t end on polling day. Now’s the time to find out what the public really want.

We might learn that the many (and there are many) sides have more in common than we think.

Dr Alan Renwick is director of the ESRC-funded citizens’ assembly on Brexit